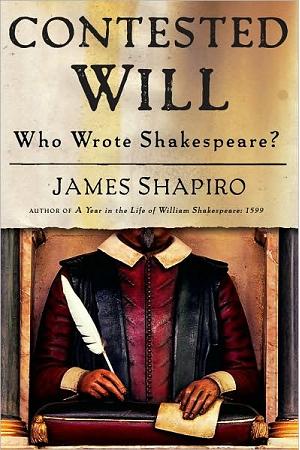

Book Review: Contested Will: Who Wrote Shakespeare? by James Shapiro

| | Clever title |

There is a fine line between controversy and conspiracy theory, and I can think of no better example of this than the Shakespeare authorship question. Perhaps you've come across somebody who manages to sneak it into a conversation and point out all these strange anomalies about Shakespeare, from the fact that he couldn't spell his own name to the notion that he didn't own any books or have enough formal education to be the famed playwright of Hamlet, Othello, and King Lear. For me, I first heard of this from a high school English teacher, and I will admit to having been intrigued. However, over the years, the authorship question sunk to the back of my mind, never to be seriously considered again until I received, as a gift, a copy of James Shapiro's new book, Contested Will: Who Wrote Shakespeare?

The book claims to be an unbiased attempt to sort the truth from the noise and examine the history, not of Shakespeare himself, but of the whole authorship debate. While Shapiro writes that he has no particular horse in this race, it becomes clear very early on that he believes that Shakespeare, the man from Stratford-upon-Avon, is the author of the works attributed to him (though he does demonstrate that writing--especially playwrighting--was far more collaborative in Shakespeare's day than most people think). However, he writes sympathetically about the various people and groups--including celebrities like Mark Twain, Sigmund Freud, and Hellen Keller--who believed in something else, that there is some sort of grand conspiracy or hoax at work and that the plays and sonnets we call Shakespeare's were written by somebody else. In short, James Shapiro bravely does what few Shakespearean scholars are even willing to consider: he engages the conspiracy theorists.

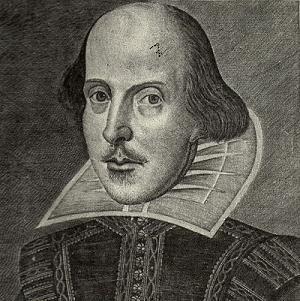

| | Wait, is that a lightning-shaped scar on his forehead? But that would mean... Harry Potter is Shakespeare! |

The result is surprisingly engaging and entertaining. Shapiro cleverly chooses not to tackle the conspiracy theories point-by-point, instead going very simply through the history of Shakespeare, outlining what is known and what isn't. For those who don't know much about Shakespeare, rest easy knowing that scholars and historians don't really know much more than you do. Essentially, all that can be proved is that William Shakespeare was born the son of a glover, lived in Stratford-upon-Avon, married, had a son (named Hamnet) who died young, worked in the theater, sued a neighbor over a minor debt, died, and was regarded as a great playwright in his day. Really, that's it. The only surviving documents relating to Shakespeare include a curious will and a handful of mundane legal documents. Anything else we know about Shakespeare comes from second-hand sources, as there are no other existing records of Shakespeare's life, almost as though the man had deliberately tried to erase himself from history.

The problem arose two hundred after Shakespeare's death, when people wanted to reconcile the few facts known about Shakespeare the man against the genius of Shakespeare the playwright. As Shapiro outlines, the controversy was born with the modern assumption that writing must be inherently autobiographical. Shakespeare's plays are full of stories of nobility, extreme human tragedy, love, violence, and virtues that couldn't be found in the humble man from Stratford-upon-Avon. For example, Shakespeare seems to have been incredibly miserly, especially late in his life, and yet his plays clearly decry the evils of greed (Shylock alone can be used to make this argument). We also know very little about young Shakespeare's education, and thus people assume that a glover's son from Stratford couldn't possibly have first-hand experience with warfare, other countries, and the troubles of princes and kings.

| | Some people even think Shakespeare was a klingon |

With all of these apparent discrepancies, it was only a matter of time before people started proposing alternative Shakespeares. The two most popular candidates over the years have been Sir Francis Bacon and Edward de Vere, the Seventeenth Earl of Oxford, people far more worldly and experienced than William Shakespeare (and people about whom we know a lot more). While Bacon was the popular choice in the early days of the authorship debate, de Vere is the most popular one today. Those who argue that Edward de Vere was the true author of Shakespeare's plays (known as Oxfordians) are vehement and loud to the point that, if you surf the web looking for information about the authorship question, de Vere's name is certain to be the first name you come across after Shakespeare's.

While Shapiro does occasionally get to the minutae, like explaining how personal libraries were often left out of wills and deeds--thus explaining why Shakespeare's will includes no mention of books--he spends most of his time on the broad strokes. He sticks to his central thesis throughout, arguing that the only way one can embrace the conspiracy theories is if one assumes that all writing is autobiographical. (Shapiro also has a secondary thesis, arguing that the Higher Criticism--more on that a little further down--is largely to blame for the debate's existence.) Make no mistakes, though, his book is incredibly well-researched and fully documented, complete with a mind-numbingly long bibliography. Shapiro has clearly done an extensive amount of historical legwork, but he rarely lets the details of his research take over his writing.

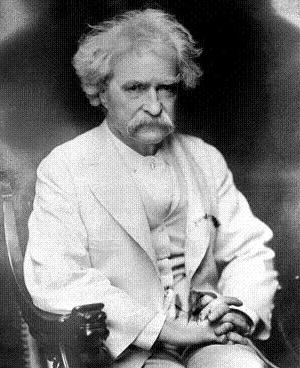

| | So if you can only write about what you have experienced first-hand, how can you write about Shakespeare if you aren't four-hundred years old like Mark Twain? |

The book is divided into four major sections. The first details the early days of the controversy, where Shakespeare historians were frequently caught red-handed in acts of the boldest and most insane frauds. This first section is possibly the most entertaining, because Shapiro doesn't tell you what is real and what is not until the point in his tale when the frauds are discovered. For anyone whose knowledge of Shakespeare the man is limited, it's easy to be duped by the stories of lost plays and attics full of forgotten documents like a letter written to Shakespeare by Queen Elizabeth herself. It's also important to get all of these stories out of the way first, to effectively demonstrate that the history of Shakespeare scholarship is filled with forgeries, misconceptions, lies, dangerous anachronisms, and some pretty bizarre acts of academic jealousy. Though Shapiro never comes out and says it, the implication is clear: when it comes to the history of Shakespeare, don't trust anyone.

The second part of the book outlines the growth and decline of the Baconians, those who believe that Sir Francis Bacon wrote Shakespeare. Shapiro spends a lot of time on the most famous Baconian, Mark Twain. Twain spent the end of his career on the authorship debate, much to his own detriment, and his enthusiasm for the subject is matched only by Twain's other obsession: himself. Twain is undoubtably one of the greatest American writers and thinkers who has ever lived, but Twain was a firm and outspoken believer in the notion that all writing is autobiographical and that nobody could write about things they only learn about in books. This is why Shapiro spends so much time on the man, because it makes perfect sense--given Shapiro's thesis--that Twain would become such a devout anti-Stratfordian.

The book then goes on to outline the Oxfordians, the most visible anti-Stratfordians today. There are plenty of people in the Oxfordian camp, so many, in fact, that they have major disagreements with each other about certain parts of their conspiracy theory. Some remain vague on the details of how or why Edward de Vere took part in such a stunning controversy, while others go down the rabbit hole of conspiratorial lunacy and start talking about how de Vere was actually the son and lover of Queen Elizabeth, that he was secretly denied his rightful place as an heir to the throne, and that was why he had to have a secret identity. Shapiro is the least sympathetic here, as he feels the facts clearly refute the Oxfordian theories, and can't hide his disappointment when he outlines the dramatic resurgence of the Oxfordians in the latter years of the Twentieth Century.

| | That's right: Homer might not be real! |

Finally, the book concludes with a section devoted to Shakespeare himself. This final section details all the second-hand knowledge we have of Shakespeare from the writers, critics, and thinkers of Shakespeare's day. At the start of this section, it seems a little unconvincing, but as he goes on, the sheer volume of documentary evidence makes his point for him: the conspiracy theory, like so many others, falls apart under its own weight. There would have to be so many people in on it that the whole purpose of the conspiracy would have been lost. If everybody knew Shakespeare was not Shakespeare, why persist in the deception?

Shapiro's arguments are extremely compelling, and his attack is refreshingly open-minded from the onset. Only in the final section of the book does it feel like he is directly arguing against the anti-Stratfordians; for the rest, he feels like a man genuinely trying to come to terms with the facts and the suppositions.

He discusses similar controversies that have popped up over the years, including the Homeric authorship debate (Homer, it seems, might not have created The Iliad and The Odyssey, assuming that Homer even existed as a human being, which is a surprisingly dubious assumption) and, more importantly, the Higher Criticism. The Higher Criticism is a name for the controversial approach to Biblical scholarship that attempts to use actual historical evidence to piece together where the Bible actually originated. In the early Nineteenth Century, only a few years before Shakespeare authorship found its first doubter, some historians were arguing that Jesus is more myth than man and that the gospels are not first-hand accounts of anything. So it makes sense that, if people are seriously saying that Homer was not Homer and Jesus was not Jesus, one could say that Shakespeare was not Shakespeare without being completely insane.

But in the end, Shapiro's central point is hard, if not impossible, to refute. The greatest error any historian can make is applying modern-day thinking to historical times. There are hundreds of little anachronistic assumptions we make about what life was like in Elizabethan and Jacobean times that contribute to the existence of the authorship controversy. Shapiro demonstrates how several of these assumptions have poisoned our knowledge of Shakespeare and why it's important, but he spends most of his time discussing the nature of writing itself. Shakespeare was an unparalleled genius, but how he wrote is very different from how people write today. His work wasn't hindered by autobiography or even a desire to have historical accuracy (in fact, Shakespeare's historical plays are wildly inaccurate, even by the standards of his day), but even if it were, it is unfair to suppose that a writer can only write from his own point of view and knowledge. A writer is God to his or her own creations--in a very literal sense--but can never be that great in his own life. Thanks in part to Shapiro's work, I see no discrepancy between a humble, flawed man and a writer of such caliber that he is still considered the greatest the world has ever produced.

FINAL SCORE:

While it won't sway the true believers, Shapiro's book is compelling, entertaining, and convincing for anybody with an open mind and an interest in the subject.

|

-e. magill 7/20/2010

|

|