Book Review: The Hidden Reality by Brian Greene

| | This is technically a review of the audiobook |

Alternate realities and parallel worlds has been a common staple of fiction for over a hundred years now, having been covered by writers such as H.G. Wells, C.S. Lewis, Piers Anthony, Robert Heinlein, and even Stephen King, among many others. It also regularly appears in T.V. and film, including in Star Trek, Doctor Who, Sliders, eXistenZ, The Matrix, and Fringe. In other words, the idea that there are universes beyond the familiar one of common experience is hardly new. Still, prior to reading Brian Greene's latest book that attempts to make hard theoretical physics accessible to the layman, The Hidden Reality: Parallel Universes and the Deep Laws of the Cosmos, I didn't give the concept much credence. I knew about the many worlds interpretation of quantum physics and M-theory's "braneworld," but I had no idea how compelling the idea of multiple realities has become to modern physics.

Greene is one of the best modern science writers, in that he does a good job making extremely difficult concepts simple enough to wrap your brain around. His previous efforts, The Elegant Universe and The Fabric of the Cosmos, were great primers for understanding some of the basic ideas in general relativity, quantum physics, and string theory, but this time around, Greene has a narrower focus. His goal, which he makes explicit from the start, is to demonstrate how theories of "multiverses" have been independantly found on the fringes of several different disciplines. Greene is not trying to convince us that parallel universes are a definite reality--because not even he is convinced yet--but he earnestly tries to convince us to take the idea seriously, because a paradigm shift in human thought and science could be just around the corner.

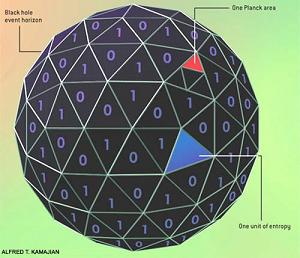

Those who have read Greene's previous books will be happy to hear that he doesn't spend as much time covering the core notions of modern science. There isn't, for example, a chapter or two devoted to explaining general relativity from scratch. He does cover the concepts that are necessary for understanding each multiverse scenario he covers, but for the things he's already dedicated time and effort explaining in his other books, Greene's overviews tend to be brief. This gives Greene more time to discuss new ideas and finer distinctions. For the dedicated layman (like myself), this is exciting, but it does make The Hidden Reality Greene's most difficult book to date. Most readers will inevitably reach a point where the science gets too difficult and no amount of metaphor can clarify any further. (For me, despite going over the chapter several times, I still don't fully understand "the holographic multiverse.") Luckily, Greene, as is typical of his style, alerts the readers to choppy waters ahead, offers a brief synopsis, and invites us to skip ahead if we want.

| | Brian Greene wants to blow your mind |

The thing is, Greene's style is so welcoming and enthusiastic, it's even fun to read about things your mind can't handle. He does his best, offering plenty of simple metaphors that lead us carefully from point to point, all the while offering brief reminders of concepts he covers earlier in the book. In the end, it is as compelling as any fictional adventure, only disappointing in the fact that there is no ultimate conclusion or denoument.

Brian Greene explains at the start that he has pinpointed nine distinct multiverse proposals, and he carefully goes through them one at a time. Rather than going chronologically, Greene begins with the easiest ones, saving the most mind-blowing for later. Though his last two multiverse proposals are more philosophical than scientific, he eagerly explains that every multiverse is a valid one to consider and cannot, as yet, be proved or disproved. This is what is most surprising about Greene's thesis, because most people's gut reaction to the idea of alternate realities is that it is the stuff of fancy and not something real science is taking seriously. In fact, though, science is taking it seriously.

Still, Greene is a vigilant skeptic, occasionally taking breaks from the journey through the multiverses to ponder whether science can ever prove or disprove them or whether it is even correct to call them scientific if they are ultimately unfalsifiable. He acknowledges that this is possible and that there is legitimate controversy among professional scientists, but he explains that most of the multiverses have come out of mathematics and extremely careful, unbiased analysis. He offers short lists of possible ways each one could be proved, disproved, or made more or less compelling, but he makes no judgments of his own, only briefly saying that, as a scientist, his mind is not set. These sections are the most critical ones in Greene's book, because it gives us a sense of what it's like on the outer fringes of theoretical scientific thought.

It wouldn't be Brian Greene, though, if he didn't spend significant time on string theory, his particular specialty. After covering multiverses that come from general relativity, inflationary cosmology, and quantum physics, he finally approaches multiverses that spring from string theory. Before he gets into those, though, he offers his longest single aside to explain the current state of string theory. He even goes over the same points with string theory that he does with the multiverses themselves: whether it can as yet be proved or disproved and if it can be considered real science. This lengthy section is the connective tissue between this book and his previous ones, in that he is updating us on things he has put forward before. Those who've been reading Greene or following string theory for years, as I have, will relish this part of the book, but newcomers might find it burdensome and irrelevant to the multiverse proposals.

| | Brian Greene's string theory should not be confused with Sam Beckett's string theory |

This is because the many varieties of multiverses being put forward are surprisingly entertaining. Sometimes, when you come to understand just a handful of concepts that have been well-established and proved by years of study and experiment, the multiverse seems almost inevitable. For example, Greene's first multiverse, which he calls "the quilted multiverse," is a logical extension of the cosmological principle and the possibility that the universe is infinite in expanse, something many scientists believe. Briefly, the idea is that, if there are a finite number of arrangements of particles in a given area of space but an infinite amount of space for those particles to fill, then every possible iteration of physical reality would be realized an infinite number of times. It's a simple concept, but its implications are startling, and that's the pattern of almost every single one of Greene's multiverse scenarios.

It almost starts to feel like a series of logic puzzles. He gives you some basic concepts (some more basic than others) before he explains how they all come together to form a multiverse. You can read along and then, just before the multiverse makes its grand appearance, you can ponder the concepts Greene has given you and try to sort it out yourself. However, as you get closer and closer to the end, this becomes nearly impossible. The last few non-philosophical multiverses, "the quantum landscape multiverse" and "the holographic multiverse" in particular, are built from concepts that are already pretty difficult to comprehend. By the time you get through the basics, if you even can, you probably won't have the capacity to see the multiverse coming.

Just as fatigue of these difficult subjects sets in, following the climactic chapter on holography, Greene tones it down and gets philosophical. His last two proposals, "the simulated multiverse" and "the ultimate multiverse," are far more familiar to those of us who've seen Star Trek and The Matrix. Thus, they are far easier to comprehend than ideas that come from the nature of entropy on the event horizon of a black hole. However, though these ideas are familiar, Greene's revelations about them are no less surprising.

| | Black hole entropy made "simple" |

For example, we are all familiar with the idea that we might one day be able to simulate consciousness in a computer and create simulated realities that feel no less real than actual reality. However, what few of us have stopped to ponder is, if it becomes possible to easily create alternate realities in a computer, complete with artificial consciousness, then we will potentially create numerous simulated realities, each populated with billions of artificial minds. This means that we are statistically far more likely to be living in a simulated reality than in the actual one, and there would potentially be no way to tell the difference.

In his last chapter, Greene talks about the Copernican Pattern, the idea that science has progressively revealed more and more insignificance to mankind's place in the universe. We discovered we aren't the center of the solar system, which isn't in the center of the galaxy, which isn't in the center of the universe, etc. For some, this is science's most unsettling aspect, but science isn't concerned with what is comfortable or easy to accept. Perhaps this is why considerations of one or more multiverses seems inevitable, because if it were easy and comfortable, we'd have already thought of it and accepted it. Brian Greene made a believer out of me that multiverses are at least possible, and he did it in the most entertaining and compelling way possible.

FINAL SCORE:

What can I say? Brian Greene is awesome.

|

-e. magill 4/6/2011

|

|