Middle School Narcissists: What TV Reflects about the Coming Generation

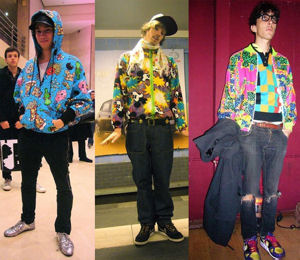

| | It is now officially impossible to stand out in a crowd |

Young people are dramatically more individualistic and less communitarian than they were a generation ago, posits a study recently published in Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace. By analyzing the most popular television shows among children aged 9-11 over the last fifty years, the authors of the study, Yalda T. Uhls and Patricia M. Greenfield of UCLA, are attempting to test the theory ("Greenfield's Theory of Social Change and Human Development") that increases in wealth and technology coincide with an inevitable shift in cultural values. Though they express concern over what this means for the future, they are not heaping all of the onus on television. Instead, Uhls and Greenfield hypothesize that the Internet and social media are largely to blame for a new, worldwide obsession with individual fame.

While I grew up watching The Smurfs, "tweens" these days are watching shows like iCarly. I don't like the idea of making grand assumptions on the basis of one or two popular shows, but it's hard to refute the study's conclusion. With the rise of YouTube and reality TV, kids have more access to the message that anybody can achieve fame and success, regardless of hard work. Even popular music seems more focused on individuals and less on whole bands than ever before.

| | Victorious: making me glad I don't have a daughter |

But is this necessarily a bad thing? Uhlas and Greenfield write, "In so far as fame in and of itself is an unrealistic ambition disconnected from academic achievement, it could undermine motivation to succeed in school and thus result in dissatisfaction later in life." No doubt rampant expectations of fame would result in a lot of disappointment and disillusionment, especially when those expectations aren't couched in the lesson that one has to study and put in massive amounts of effort to achieve one's goals. Still, isn't the drive for individual success at the heart of the American dream? Isn't that the fuel that charged our collective engine through the Cold War and into the 21st Century?

It seems to me that there's a vicious circle at work here. Individual success drove Mark Zuckerberg to found Facebook, which has given hundreds of millions of people an outlet for their narcissistic need to be recognized as individuals. It isn't possible for each of 800 million people to be famous, but that much drive and ambition is certain to produce tangible, beneficial results, even as it inevitably disappoints those who fail to shine.

The problem, of course, is that for every person who deserves his or her fame, there are several other people who become well-known for no easily discernable accomplishment. For every Stephen Hawking, there is a Snooki, and for every Steven Spielberg, there is a Quentin Tarantino. As Uhls and Greenfield point out, the problem is that, on the Internet and with idols like Hannah Montana, hard work isn't seen as a necessary component for fame. The harsh truth, though, is that it really isn't. What I find much more depressing than millions of people upset that they didn't become famous for no reason is the millions of people who are working hard, perpetually unrecognized and forced into quiet mediocrity.

| | The jackass paparazzo taking this picture has more right to be famous than the subject |

It may be our priorities, not our values, that are twisted. Why do we reward people for making asses of themselves while largely ignoring the hard workers that make our way of life possible? Why do we make celebrities out of those who entertain us while we refuse to make eye contact with the men and women who collect our trash? Why do we pay athletes ridiculous amounts of money and pay our teachers a relative pittance?

I point this out, not because I disagree with the conclusions of Uhls and Greenfield's study (I think they're probably right), but because I think the problems of society are too easily and too often watered down. Studies like this are incredibly useful and important, but the headlines usually boil down to "Television Turns Children into Douchebags" rather than exploring the nuances and subtleties. This, too, is probably a side effect of the Internet age. With so much information in front of us, who has time to read every study?

Neither television nor the Internet, however, is wholly responsible for making our culture more self-absorbed than ever before, just like it's not Simon Cowell's fault that people flocked to American Idol (or The X Factor, where now even tweens can make it big). The ebbs and flows of societal change are dictated by incredibly complex, interacting systems that reinforce and reflect each other. It is ultimately unpredictable, just like the whims of fame and fortune, and what this study really means for the future is impossible to anticipate.

| | Diane McMurray, refuse collector, would make a pretty good role model |

Besides, there are some other interesting results hidden in the data. The study identifies sixteen values that are represented by popular television, among which are "fame" and "community feeling." From 1967 through 1997, "fame" ranked near the bottom, whereas in 2007, it ranked at the very top, while "community feeling" dominated the rankings from 1967 through 1997 only to drop down to number 11 in 2007. However, it is worth noting that one value, "physical fitness," ranked sixteenth in 1967, 1987, and 1997, but rose up to number 9 in 2007. If the fame and community feeling indicators predict a future of depressed failures, at least they'll be physically healthier. Additionally, "conformity" dropped in importance and "achievement" went way up. The one incredibly important value that seems to be missing from this study is "hard work," and that is an unforgiveable oversight.

What I take away from this is that societal change should not be viewed as inherently negative or positive, regardless of what those changes are. One generation's values are never the same as the next generation's, and while we can try to mold our children in our own image, they will develop their own paradigm. I do not value the exact same things my parents do, nor do my parents agree with my grandparents on what is important and what is not. I will do my best to ensure that my son's morals and values are worthwhile and healthy, but I should not expect that he will perceive the world the same way I do.

-e. magill 10/4/2011

|

|