Metro 2033: Differences between the Novel and the Game

| | Why are the letters all weird? |

A film professor once tried to explain to me that the best way to understand what makes film a unique storytelling medium is to compare and contrast it to other artforms through the adaptations it creates. Film has been around for so long that few people alive today remember when it wasn't considered a serious artform, and nowadays it's easy to find examples of movies based on novels, on stage plays, on historical events, on television shows, on comic books, on comic strips, on newspaper articles, on children's toys, on board games, on trading cards, and even on famous paintings. Using these examples, it's easy to figure out how film is a stronger medium in some ways and a weaker one in others; it's easy to discover what makes it special.

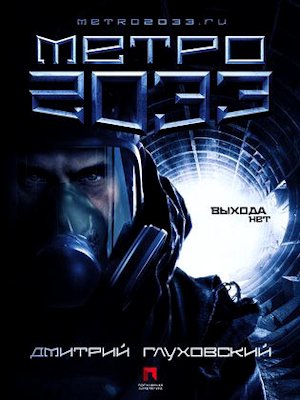

With the unfortunate passing of Roger Ebert--one of the last, most vocal holdouts of his generation--the raging debate over whether video games can be considered a legitimate artform is inexorably reaching its end, and in another generation or two, it will be as universally accepted as film is today. Therefore, with the blooming artform still in its infancy, we should try to figure out what makes it a unique storytelling medium, and just as with film, looking at adaptations is the best way to go. Video games based on movies are a dime a dozen (although, really, if you bought a dozen of them for ten cents, you probably got ripped off), but much rarer are video games based on novels. The most widely-known recent example is Metro 2033, the 2010 game based on the Russian novel of the same name by Dmitry Glukhovsky. Having played through the game and read through the novel (though not either's independent sequel), I am startled by their unexpected--but instructive--differences and similarities.

For those not familiar with the story (there will be spoilers ahead), both the novel and game take place mostly in the subways beneath Moscow in a post-apocalyptic near future where the surface is unfit for human habitation. The residents of the Metro may be the only human beings left alive after nuclear fire rained down on the world for reasons that have been lost to history, and they have to contend with all manner of obstacles just to keep on surviving. The story follows Artyom, a young man who traverses across the various stations of the Metro in order to find help in defeating a new and unprecedented menace that is attacking his home station from the surface: strange and powerful mutant creatures with apparent psychic powers dubbed "the dark ones." Along the way, he encounters several strange people, micro-societies, and seemingly inexplicable, supernatural phenomena.

The Enemies

| | Replace this with a Jehovah's Witness and the stories are exactly the same |

The Metro 2033 video game features a wide array of enemies for Artyom to contend with, starting with giant ratlike creatures called "nosalises" that appear everywhere. It makes sense, as the game is primarily a shooter, to have a lot of things for Artyom to shoot at, including huge winged demons, pack-like hunters called "howlers," violent human enemies like fascists and militant communists, gorilla-esque monsters called "librarians," and strange electrical "anomalies" (though shooting at anomalies is a bad idea). There's even a final boss of sorts in the giant, oozing biomass that protects the inner sanctum of the Metro. By the end credits, Artyom has no doubt killed several hundred baddies.

You might expect the novel to either have all of these or none of them. Indeed, by the end of the novel, Artyom has only killed a handful of times. He kills one fascist in a fit of rage, euthanizes a friendly companion, and takes out perhaps a half-dozen creatures on the surface. He does carry a gun through most of the story, but he rarely has to use it, because most of the enemies from the game--most notably the omnipresent nosalises--do not appear anywhere in the novel. I was also surprised to discover that the anomalies are nowhere to be found, since they seem so oddly out of place in the game. Aside from those two examples, though, all the other creatures do make an appearance, though not until late in the story. Even the game's final boss--the biomass--appears in the novel, though it is quite different; in the book, the unnamed biomass appears under the Kremlin, moves more like a gelatinous liquid than a solid mass, and has strange psychic powers that take control of Artyom and the men who are accompanying him. The human characters in the novel are a little less violent as well, though not as much as you might expect. The novel gives you a better sense of how important it is for people to survive, and Artyom isn't the prodigious killing machine he is in the game, but there are still murderous fascists, along with a wide range of other human factions, some of which are even worse.

A video game such as Metro 2033 has both the obligation and the freedom to have many enemies for the protagonist to face (and kill). Though imaginative monsters certainly exist in novels, a book can only get away with describing so many before they start to get tiresome. Neither mode is inherently better overall because of these differences, but each is better suited to a particular type of storytelling. Zombies, for example, are incredibly ubiquitous in video games and movies, because they are right at home in an artform that relishes giving people a large number of things to kill or run from, but that doesn't make them any less useful as an all-purpose metaphor. You don't see things like zombies nearly as often in the more passive arts like novels and plays, because those artforms are more cerebral, better suited for singular horrors like Frankenstein's monster or the Phantom of the Opera. I have little interest in reading a novel about zombies, just as I have little interest in playing a video game about the Phantom.

The Factions

| | Hitler's mistake was just that fourth arm on the swastika |

One of the most interesting things about the novel is how many different socio-political ideologies are represented in the Metro. There's a long, bloody history between the two main factions--the capitalistic Hansa and the communistic Red Line--but each and every station seems to have its own unique spin on life and civilization. There are the aforementioned fascists, of course, skinheaded Russians who follow the old German model of Nazism and call themselves the Fourth Reich, and they are constantly being needled by a group of self-made revolutionaries who idolize Che Guevara. In addition, Artyom comes across a post-apocalyptic branch of the Jehovah's Witnesses, an anarchistic station that refuses to even dictate the time of day to people, a large "city" that obeys an Indian-style caste system, and savage cannibals who worship a new diety they call The Great Worm. He also hears tales of satanists trying to dig down to Hell itself, an isolated society run by university professors and intellectuals, and more. What Glukhovsky creates is an ingenious microchosm, and he fills it with as much variety as he can imagine, careful not to make any of them come across as utopic. Anybody fascinated by world politics has more than enough to chew on here, and Glukhovsky's brilliant in his neutrality (religious people, though, might take issue with the novel's negative take on organized religion).

Naturally, the game streamlines most of this away. The Hansa, the Red Line, and the Fourth Reich are all represented, but most of the other mini-societies from the novel are gone. Patient and diligent gamers might come across the occasional line of stray dialogue that references some of these other factions, but they are mere easter eggs that serve no narrative purpose of their own. As a result, you don't really get a sense of Glukhovsky's microchosm, nor does Artyom spend enough time with any of them to really draw any conclusions about how society can operate under these new and brutal conditions. The game also completely does away with the heavy religious overtones of the novel, which simply reflects how rarely gamers want more controversial religious considerations thrown into their games.

Video games, by necessity, can't be as ponderous or thought-provoking as a novel can, and this is a prime example. Metro 2033 is a Russian novel to boot, so one should expect it to have long passages where the main character considers philosophy, religion, and the meaning of life. At least 50% of the novel is devoted to such meanderings, which is perfectly fine for a novel, but if the video game were to follow suit, people would stop playing it after twenty minutes and never feel the desire to go back to it. Games can certainly have deep socio-political subtexts and themes--see Bioshock for example--but they must have action, first and foremost, whereas a novel can quickly get bogged down by too much action and not enough commentary. I wouldn't want to read a novel based on Bioshock that included descriptions of every single splicer death I witnessed when I played through the game, but I would want to read one that had a deeper exploration of the game's backstory and thematic underpinnings.

The Horror

| | Yeah, that, that's not right |

When I picked up Metro 2033, the game, I did it because I'm always on the lookout for new and interesting suvival horror, a genre that has been getting increasingly rare of late. Though it's not one of the best survival horror games of its console generation, it does have a few cool tricks up its sleeve that make it noteworthy. The single most brilliant spin on the formula is the way ammunition is used as currency within the Metro, but the game also manages to illicit a fair amount of dread in its dark corridors full of unspeakable horrors and unknown dangers. Even the surface world is nerve-racking. In a couple of places, Artyom has brutal hallucinations that blur the line between what is real within the game and what is in the protagonist's head, and that only adds to a general sense of unease that fills the entire game from beginning to end.

This is where I think the game actually exceeds the book. Though all the ingredients of horror are present in Glukhovsky's original work--the dark setting, Artyom's terrible hallucinations and vivid dreams, the constant unknown threats that lurk around every corner--I never found the book to be all that frightening. There are one or two stand-out scenes (notably, the library and Artyom's subsequent flight from the hunter creatures in the streets and alleyways of the surface), but the book is more focused on setting the scene and describing the universe than on filling the reader with dread. (The ending is pretty damn bleak, but I'll get to that later.) Surprisingly, though, I will admit that the novel does reflect the survival half of the survival horror formula. Artyom is always battling scarcity--he looses his passport near the middle of the story, for example, and that becomes a plot-altering obstacle for him--and just like in the game, his ammunition is Metro currency. As a matter of fact, with its long expositions describing what people have to do to survive in the Metro, the novel makes it clear that survival is everything.

When it comes to horror, the written word, in general, is lacking. I have never been truly frightened by a novel, no matter how well-written, though I admit without shame that a good horror movie or video game can have me sleeping with the lights on. It's not that novels aren't immersive--in some ways, I think they're more immersive than any other artform--but they simply cannot be as visceral. Movies and games can shock you with terrible imagery and sounds that you aren't prepared for, whereas if you read a description of something terrible in a book, the horror is limited by your own willingness to imagine it. I could, for example, describe a deadly spider with grotesque detail for pages on end, but it will never torment you the way a video of raining spiders can (assuming, of course, you hate spiders as much as I do). Video games take it even further, because there is a heightened sense of personal danger. You, as the main character, are free to die in the most mind-shatteringly messed up ways at the drop of a hat. If somebody made a video game where you are under constant threat of being slaughtered by hordes of giant spiders, I would never play it because it would be too scary, but if you wrote a book about hordes of giant spiders, I could read it before going to bed and be totally fine.

-e. magill 9/10/2013

|

|