The Summer of Arthur C. Clarke: 2001: A Space Odyssey (film)

Before I begin, welcome to my Summer of Arthur C. Clarke. On the heels of last year's popular Slasher Summer, this year I'm leaving behind the guilty pleasure of the niche horror genre and exploring something a little closer to my own heart: namely science-fiction. Of all the sci-fi greats, none have influenced me more than the late Arthur C. Clarke, my personal favorite of the "Big Three" from the Golden Age of the genre (Asimov, Clarke, and Heinlein). This summer, I am going to look at a few of his most famous works, including the entirety of his 2001 series and the tiny handful of adaptations that have been made for film, television, and video games. Strap in and prepare yourselves for a journey into the stars and the mind, and let us never forget how much richer the world of fiction is for having been blessed by the incomparable Sir Arthur C. Clarke.

| | If you don't automatically hear "Thus Spake Zarathustra," I don't understand you |

There is an important line, albeit a blurry one, to be drawn between art and entertainment. Many people make the mistake of watching Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey as pure entertainment, and they tend to walk away from the experience a little perplexed and exhausted. I've gotten a lot of flack in recent years for stating my opinion to anyone who asks that 2001 is, in fact, the greatest science-fiction film ever made and possibly ever will be made. Justifying this opinion is hardly my goal today, as I consider it closer to a matter of simple fact than one of personal preference.

You could fill several college campuses with the scores of academics, scholars, film historians, and writers who have devoted years to penning volumes of articles and books about 2001, including my own father-in-law, a film professor and noted Kubrick analyst living out his semi-retirement in South Carolina. There's little I can write about the film, if anything, that hasn't been written before, and I have to measure my words carefully as the aforementioned father-in-law will no doubt correct any mistakes or misconceptions I may have on the subject.

In the mid-to-late-sixties, before man walked on the moon, Kubrick and Clarke set out to make "the proverbial good science-fiction movie," and they worked together for a considerable amount of time to make it happen. When comparing novel to film, it's difficult to parse out which is being adapted from which, as the two share a symbiotic relationship, having been created at roughly the same time and having fed off each other throughout their twin gestations. (For a detailed break-down of the process, read Clarke's own The Lost Worlds of 2001.)

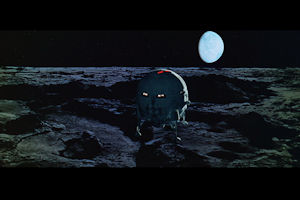

| | If Kubrick really had faked the Apollo 11 moon landing, it would have looked way better |

Still, it's clear that each version of the story is attempting to accomplish something different. Clarke's novel is more intent to enlighten through scientific fantasy, whereas Kubrick's film is striving to wordlessly show something profound using the unique tools of his chosen medium. Both deal in weighty themes, but Kubrick's film feels more relevant and universal as it uses the silver screen to reflect the deepest, most instinctual core of our own humanity, its evolution, and the tools it uses to both create and destroy. In other words, 2001 the novel is more on the entertainment side, whereas 2001 the film is firmly planted on the art side.

The film is a lucid dream that washes over you, if you let it. It speaks more to your unconscious mind than your waking intellect, and it bypasses preconceptions both subtle and gross to sow the seeds for thoughts and feelings that grow long after the credits have rolled. While I could spend literal days, if not weeks, going over all the themes, motifs, and ideas the film is trying to convey while explaining exactly what's happening in the narrative and what every scene and seemingly miniscule bit of symbolism probably means, my advice to those of you who don't "get" the film is to stop trying so hard to understand it. Rather, just experience it.

Then again, if you absolutely must grapple with its meaning, reading Clarke's novel isn't a bad starting point. At the very least, it will help make sense of the more difficult parts of the narrative. It won't help too much with Kubrick's underlying themes, as the film and novel deal in different ones, but I find it relatively easy to pick up the basics from just one or two viewings, even if you aren't well-versed in hardcore film analysis.

| | I could talk about just this chess match and what it means for over an hour |

But seeing as how this summer is devoted to Clarke, not Kubrick, let's try to stick with what the film has to say about his body of work. If you look at the film as an adaptation of Clarke's novel, it is clearly the superior product, not because of any changes (indeed, most of the changes, such as placing the monolith in orbit around Jupiter instead of sitting on a moon of Saturn, were made for practical reasons, like the fact that Kubrick simply couldn't get Saturn to look good enough to meet his insanely high standards of visual quality), but because the film elaborates on Clarke's ideas to reveal insights about his story that you'd be hard-pressed to find even in a deep overanalysis of the subtext.

As I mentioned last week, I feel Clarke's novel is a meditation on the nature of consciousness, which Kubrick uses as a launching point to explore the nature of agency, of technology and violence as byproducts of the type of consciousness Clarke describes. At the same time, Kubrick is trying to advance a genre of filmmaking that, if we're speaking honestly, hasn't fully learned the lessons he tries so earnestly to teach. He does this not by arrogantly proving he knows how to make better films than nearly everyone else (even though, yeah, he absolutely does), but by applying Clarke's hard sci-fi approach to filmmaking.

An oft-repeated anectdote about 2001 is that Kubrick ensured all of his space props--aboard Space Station V, at Clavius Base, on the surface of the Moon, and aboard the Discovery--would all function properly in their respective locations. The spacesuits in the film, in other words, would actually protect people from the vacuum of space. That's a ludicrous attention to detail, rivaling the notoriously fastidious Erich von Stroheim when he famously forced his extras to wear historically accurate underwear for the ten hour epic Greed. While it is true that Kubrick was a stickler for insane levels of detail in other films, here it is a cinematic echo of one of Arthur C. Clarke's hallmark qualities: realism always trumps artistic convenience.

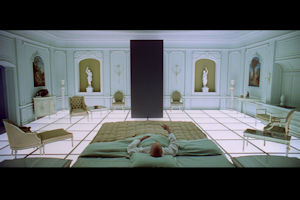

| | Bowman reaches for the monolith exactly as Moon-Watcher does |

Kubrick is no more willing to compromise than Clarke, and it shows in all the film's little touches. Even something as basic as ensuring there is no sound in space is usually overlooked in other science-fiction films. Kubrick doesn't fudge on gravity, either, even though it would have made his production much simpler and cheaper if he hadn't needed to build the complicated gimbles and invisible harnesses that ensure his film still holds up against modern CGI and rotoscoping techniques.

Clarke was also influenced by Kubrick, although it was more of a long-term effect. You can see it in his writing, when you compare everything that came before 2001 with everything that came after it. He would become less devoted to conventional narrative (not that he was particularly devoted to it to begin with) and more to his scientific propriety, and he made more of an effort to weave artistic and thematic elements into his work where they hadn't been before. Thus, the creation of 2001 is an example of a rare creative synthesis, the kind of harmonious collaboration that strengthens both participants, and it's no wonder that Clarke would, in later years, continue to collaborate with others in a vain attempt to recapture the magic he made with Stanley Kubrick.

-e. magill 6/7/2018

THE UNAPOLOGETIC GEEK'S

SUMMER OF ARTHUR C. CLARKE: | |

|

|

|