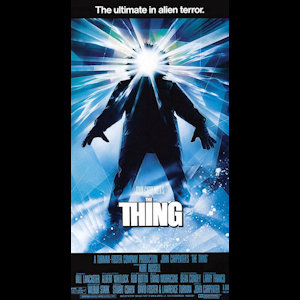

John Carpenter's The Thing - Sci Fi Classic Film Review

Welcome to THINGTOBER! A hostile alien has been revived in a remote Antarctic research station, and we have just one month to deal with it. Starting with John Campbell's classic novella "Who Goes There?" and then carefully dissecting the three films based on its ideas--The Thing from Another World, John Carpenter's The Thing, and 2011's The Thing--we will try to determine what makes this terrifying monster tick and whether or not we can ever be sure it's not right next to us, poised to take over the world.

| | It's not a vegetable this time |

Out in the bitter snow and freezing silence of the far North, Metereologist George Bennings looks out at his colleagues at the Antarctic Research Outpost 31, all gathered around him in a half-circle. They look at him with the barest of emotion, more perplexed than anything, paralyzed by a combination of fear and anxiety. One of his colleagues, the helicopter pilot R.J. MacReady, has just kicked over a drum, spilling gasoline towards Bennings as he kneels before them all in judgment. Bennings lifts up his arms in surrender and lets out a howling plea, but none of his other colleagues make any moves to stop MacReady as he throws a lit flare at the pool of petroleum, setting him alight and killing him in one of the most brutal and painful ways possible. This is because Bennings is not Bennings; he is The Thing, a half-transformed alien being who has assumed the physical body and identity of Bennings.

This moment, which occurs roughly half-way through John Carpenter's The Thing, is key to understanding what makes the film so effective. In one brief, panning shot, the camera gives us the perspective of the Bennings-Thing, with the men around him all looking directly at the camera. There are surprisingly few direct POV shots like this in the movie, and this one is a deliberate choice to show what it is like when people look at you with a total and complete lack of one critical human element: empathy.

A few plot choices early in the development of this adaptation of Campbell's "Who Goes There?" contribute to the psychological horror. One, the size of the crew around which the story revolves is greatly reduced. Two, the first act of the script takes its time to develop the central problem so that audiences have time to get to know a baseline for how these characters interact. Three, the characters are made distinct and each is given a flaw or two to help make them feel real. And four, the characters are written with a minimum sense of comraderie; they are capable of working together just fine, but generally speaking, they don't seem to like each other all that much. (Most of us have had jobs like that.)

| | They just gawk at you silently as the boss burns you alive |

In the original story and especially in the 1951 adaptation, The Thing from Another World, the crew is more cohesive and the men draw strength from their mutual respect and friendship. Taking that away makes the paranoia so much more powerful, because it makes it frighteningly believable that the barriers of empathy that keep us from turning on each other are more fragile than we like to believe. Virtually everything in John Carpenter's version of the story contributes to our characters losing their empathy: little plot details like the unsolvable mystery of the keys; the fact that the man who should be their leader, Commander Garry, is a wimpy officer who probably wound up in Antarctica because of debilitating PTSD; and the strong specter of doubt foisted on the protagonist, MacReady, through a piece of holey wardrobe. By the end, it seems entirely plausible that anyone who survives would never be able to trust a fellow human being again, which is reinforced by the hauntingly open-ended final scene.

While this is a fanciful sci-fi tale about a shape-shifting alien, it is primarily a story about isolation, both physical and emotional. Like the Bennings-Thing unable to draw out even a hint of pity from the crew as MacReady burns it alive, each man at the outpost must face a reality where he cannot rely on anyone but himself, where his fellow man could turn homicidal toward him based on nothing but suspicion and innuendo. This is also why the setting is so profoundly effective: few other places on Earth, if any, could make a man feel as alone as the middle of Antarctica.

There are many reasons why John Carpenter's The Thing is a great film, but I truly believe everything--the clever writing, the brilliant practical effects, the detail-oriented set design, the moody, minimalistic score, the muted colors and dramatic lighting, the lack of an opposite sex, the deliberately confusing scene transitions--flows from this central thematic concept. Carpenter wants the viewer to experience complete isolation where nothing is certain and nobody is trustworthy. That disturbing uncertainty is also why the film has endured for so long: you unconsciously want to prove the story wrong, want to prove that, through a combination of attentiveness and reason, you can deduce exactly what is happening and who is worthy of your empathy.

| | "You've got to be fucking kidding me" |

And I can play that game all day. I love going over this movie with a fine-toothed comb trying to parse out the airtight evidence that will provide final proof about who is a Thing and when. I can list all kinds of tantalizing details that just feel like they should be critical to understanding something (as I did in a previous article). For example, take the scene where the Norris-Thing's disembodied head is crawling on giant spider legs out of the room where the rest of its body has just been immolated by MacReady. It is Palmer who brings everybody's attention to it just before it gets away, leading to its immediate disposal, but then, in the very next scene (the blood test sequence), Palmer is revealed to be a Thing as well. Why would the Palmer-Thing deliberately stop the Norris-Thing from getting away? Does this prove a human Thing doesn't know it's a Thing, or does it prove that the Thing is a master at misdirection who is willing to sacrifice one of its own in a gambit towards ultimate survival? It's maddening, because the answer that seems so close just never materializes. Every detail and every scene can be read in multiple ways, and no one way is ever definitively proved correct.

But as fun as it is to rip apart the movie looking for answers, it's not what I'm here to do today. I'm here trying to figure out why this film--which was a critical and box office disaster on its initial release--has survived so long with such a strong reputation for being one of the best science-fiction horror films ever made. And while I'd love to conclude that the answer is how it shows people turning on each other, I think it goes just a little bit deeper, and is a little bit more unnerving.

It goes back to that shot, from the Thing's POV right before MacReady burns it to death. While virtually every assumption made by the characters is the subject of fierce debate among fans, one assumption that always seems to be uncontroversial is the idea that the Thing is inherently bad. I think this reveals an even more upsetting lack of empathy, a refusal to even consider the possibility that the Thing is the victim here, that the human characters are the ones committing remorseless murder and destruction. The look they give the Bennings-Thing is utterly terrifying if you consider the possibility that the Thing is begging for help. The characters are staring at the camera--at you--without any sort of mercy or sympathetic warmth as they kill you. If that's not scary, I don't know what is.

-e. magill 10/18/2018

THE UNAPOLOGETIC GEEK'S

THINGTOBER: | |

|

|

|