"The Things" by Peter Watts - Short Story Review

Welcome to a bonus segment of THINGTOBER! A hostile alien has been revived in a remote Antarctic research station, and we had just one month to deal with it. Starting with John Campbell's classic novella "Who Goes There?" and then carefully dissecting the three films based on its ideas--The Thing from Another World, John Carpenter's The Thing, and 2011's The Thing--we tried to determine what makes this terrifying monster tick and whether or not we can ever be sure it's not right next to us, poised to take over the world. This week, with October officially over, we take one last look at this creature through Peter Watts' short story retelling of John Carpenter's The Thing, called "The Things."

| | He doesn't seem shady at all |

Canadian author Peter Watts is known for creating imaginative alien lifeforms. A former marine biologist, he is probably best known for his Hugo Award-nominated novel Blindsight, but he's also earned wide acclaim for his short fiction, including "The Island," which won the Hugo, and the subject of this week's examination: "The Things." I note all of this because it's important to remember that Watts had already built his career when he penned "The Things," so you shouldn't dismiss it out-of-hand as fan faction. (Not that I, a self-published novelist working on a screenplay for Metroid, has any standing to complain about fan fiction.)

Instead, think of "The Things" as an experimental offshoot of John Carpenter's The Thing, a non-linear retelling of the same story, this time from the perspective of the eponymous Thing as it tries to comprehend humanity. It's a story that wholly embraces and respects the classic film, and it stands as the perfect bookend to THINGTOBER, which started with an examination of John Campbell's "Who Goes There?"

As a short story of its own, "The Things" is difficult to get a handle on. There's very little in the way of narrative structure, with most of the action referred to rather than explained, as it presupposes a certain amount of familiarity with the 1982 film. This is more of an internal monologue that explains events as the Thing sees them, offering a few surprising revelations about the nature of the monster without devolving into tiresome over-explaining or cringey fan service. I haven't done any diagramming or super-careful analysis, but from what I can tell, it never breaks continuity: its explanations appear to hold up to scrutiny.

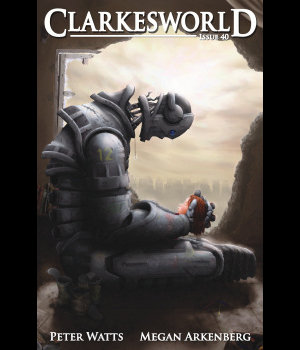

| | The magazine in which the story can be found |

Watts also hones in directly on what we talked about a couple of weeks ago when discussing John Carpenter's The Thing: empathy. This story spends practically its entire length on trying to build empathy for the Thing, in trying to get readers into its complex mind and realize just how terrifying and confusing these events are from that point of view. The Thing is seeking "communion" with humanity, and it doesn't seem to understand why the people it communes with react so violently and fiercely.

Most fascinating is how absolutely alien it makes humans out to be. The Thing has been to multiple worlds and experienced multiple alien lifeforms, but humanity is the first sentient species it has encountered that doesn't shapeshift. We are apparently an anomaly of evolution, as utterly bizarre to the Thing as the Thing is to us. As a creature with intelligence spread out through its cells, it sees the concept of a brain--the seat of human intelligence--as "cancer." It thinks of humans, therefore, as zombified lifeforms who have succumbed to aberrant growth and been frozen in place, cut off from what the Thing considers to be true sentience.

This is all excellent and fascinating, but what truly sells it, what truly makes this short story worthy of its Hugo nomination, is the final sentence. That sentence pulls the rug right out from under the reader. After pages and pages of building empathy and seeing things the way the Thing sees them, Watts reveals that the Thing is still a visceral, existential threat to humanity. The Thing concludes that it must save us from ourselves, by "raping" enlightenment into us.

| | What we really need, though, is the LEGO adaptation |

It also demonstrates Watts' mastery over diction. His word choices are deliberate and precise, and though it takes a while to get the hang of the Thing's "voice," it flows quite naturally and understandably without breaking the fourth wall. This is no easy task, but Watts makes it effortless. There is a trance-like quality to the story that works best upon a second or third reading.

In other words, it's far better written than "Who Goes There?," a short story that might be better as a full-length novel (which apparently exists, though it hasn't been released to the public yet). Campbell deserves credit for inventing the Thing, no doubt, but Watts almost reinvents it here by delving deep into its biology and psychology in a way that Campbell never even dreamt of. Still, Watts' thought experiment shouldn't take anything away from the Thing. It still stands as an enigmatic metaphor, an allegorical cautionary tale that can be applied to just about anything. It can be about political paranoia, mental illness, AIDS, the difficulty of compassion, fear itself, or a hundred other big ideas you care to apply to it. Campbell should get all the credit for that, though Watts should be applauded for not taking any of it away.

Though its answers will never be canon to me, Peter Watts' "The Things" deserves standing within the franchise that Campbell built. Fans of Carpenter's film should read it immediately, and then read it again. (It's freely available online!) At the very least, we should all be able to agree it's better than 2011's The Thing.

-e. magill 11/1/2018

THE UNAPOLOGETIC GEEK'S

THINGTOBER: | |

|

|

|