The Body Snatchers by Jack Finney - Sci-Fi Classic Review

| | That's murder on your back, man |

Dr. Miles Bennell has a problem. Lately, a handful of patients have come in with a peculiar complaint, that friends and family have been suddenly and inexplicably replaced by imposters. He refers this problem to his go-to psychiatrist, who is utterly perplexed by the phenomenon and labels it a form of mass delusion. However, Miles slowly begins to uncover the mysterious origins of the alleged delusion, learning that, in fact, people are being replaced, and he must race to save his friends, his town, and the woman he loves from an unusual invasion from beyond the stars.

This is, of course, Jack Finney's The Body Snatchers, a story that has permanently planted itself in popular culture. Adapted into big budget Hollywood films not once, not twice, but four times (we'll get to those in the weeks to come), this novel--originally published as a serial--remains Finney's most well-known work. Like John Campbell's "Who Goes There?" and The Thing (subjects of last month's THINGTOBER), it's the story of an alien invasion by a creature capable of mimicking us almost perfectly. It is also a study in human psychology and paranoia, and it has remained popular for generations because it taps into something deep in our collective unconscious. (It even reflects a very real, very well-documented psychological phenomenon called the "Capgras delusion.")

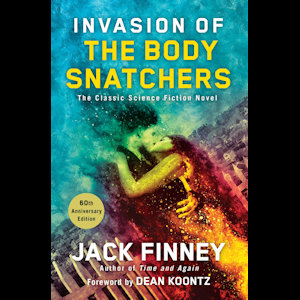

The popular interpretation is that this is a book about the red scare, fascism, or any of a number of political movements that have turned neighbor against neighbor since time immemorial, but there's little, if anything, in the text to support such a view. Finney himself vehemently rejected it. In the 60th edition foreword by Dean Koontz, Koontz posits the titular body snatchers are a reflection of technology chipping away at our humanity, and this is a little more supportable with a few lines Finney writes about how the telephone is evolving or about how things are progressing "these days." For me, though, I think it goes even deeper, because honestly, people have been disingenuous to each other since before we even developed language.

| | This is where vegans come from |

There is one incredible little anectdote thrown right in the middle of the book that gives the game away. Miles, from whose first-person POV the entire story is told, is reminiscing about an African-American shoeshine named Billy who seemed to everyone whose feet were touched by him to be the most genial, friendly, and happy human being on planet Earth. Billy always had an endearing nickname for his customers, got to know them and compliment them, and seemed less interested in the money they gave him for his services than in making human connections. One morning, Miles overheard Billy speaking to his friend in the less socioeconomically prosperous part of town where Billy lived, and the shoeshine repeated his well-rehearsed banter and nicknames with the most bitter, jaded, and hateful sarcasm he could muster, proving that, beneath the genial veneer he showed when shining shoes, he held nothing but contempt for his job, his customers, and his place in life. When Miles realized this, he felt sorry for the entire human race, believing we had all failed, and Billy was simple proof of it.

The Body Snatchers takes place in the small Californian town of Mill Valley, where most everybody knows one another, at least in passing, and Dr. Miles Bennell, as one of the few general practitioners in town, is especially familiar with the populace. When the citizens of Mill Valley begin to change, nothing readily apparent seems altered, but every small town oddity and heartwarming quirk of rural life takes on a sinister overtone, as though the entirety of the town is a flimsy façade pasted over the social equivalent of psychopathy. (Calling the snatched citizens "psychopaths" isn't too far from the mark, given their ability to mimick emotion without really feeling it.)

Cleverly, Finney's style here is very conversational, written the way you'd expect a well-educated small town doctor to talk to you when relating an embellished story. There's a charm and ease to Miles' voice that is as disarming as it is unreliable, and that reflects the story's dual motifs of homespun Americana and paranoid uncertainty. Miles also tells his story with plenty of disclaimers, acknowledging the unbelievable with reassurances that he, himself, can't be sure of his perception, his memory, or his conclusions. There's a deep undercurrent of skepticism throughout, and it makes sense coming from the mouth of a scientifically-trained doctor. It also adds realism to a pretty good romance between Miles and the female lead of the novel, Becky Driscoll.

| | My copy has the worst cover |

Though better written than Campbell's "Who Goes There?," The Body Snatchers has a few hang-ups and narrative problems that are completely different. Primary among these is a disjointed sense of time. The story takes place almost entirely over the course of three or four days, but there comes a point where the town of Mill Valley is transformed into a dying town full of decaying roads, dried up store fronts, and an overwhelming sense of creeping decrepitude that could not possibly occur over such a short period. When I read this, I had to go back and make sure I hadn't missed an odd time jump, but sure enough, our characters leave the area for a single night before coming back to what is essentially a ghost town, and that doesn't work.

Problematic too is the character of Becky. She is admirably written--and even gets a wonderful badass moment of her own that is especially notable considering the book was written in the fifties--but for a big chunk of the final several chapters, she is mere set dressing. She follows Miles around wordlessly, falling so far into the background of events and Miles' internal monologue that it's easy to forget she's even present. It feels as though an earlier draft had her written out of the climax entirely--there's even a scene where Miles tries to dismiss her for her own safety that immediately precedes this long sequence of her being quiet and meek--but a subsequent draft had him write her back in, without really including her much in the actual plot. This is especially weird given how much of Miles' character is driven by his growing attachment to her.

One more big problem the book has is its ending, which though telegraphed right from the start, feels cheap. (Alien invasion stories have had persistent difficulties like this since H.G. Wells' War of the Worlds.) Despite spending the entire novel building up a bleak realization of just how insurmountable and unstoppable the invasion has become, the final pages detail the inexplicable flight of the invading seed pods at the first real sign of resistance, leading to a happy ending where no more people are replaced, life is able to resume apace with no one the wiser, and the town of Mill Valley is slowly able to recover from its near destruction at the hands of alien municipal apathy. This is done in service to another earnest theme Finney is trying to convey: despite science's certainty about the physical world, weird things happen all the time and can't be explained away. I have philosophical problems with this theme and its assumptions about both science and nature (I'm pretty dubious about Finney's scientific literacy in multiple places), but setting those aside, this theme rings hollow in the face of what happens throughout the novel.

Despite these flaws, however, The Body Snatchers remains a bonafide science-fiction classic and earns its spot in pop culture history, even without the more well-known film adaptations. Finney wrote plenty of other novels and short stories that deserve recognition--such as From Time to Time--and perhaps I'll get to those in due course. In the meantime, I'll be spending the better part of the remaining year on the aforementioned adaptations, from the 1950's classic all the way to the largely forgotten 2007 thriller. See you next week!

-e. magill 11/22/2018

|

|