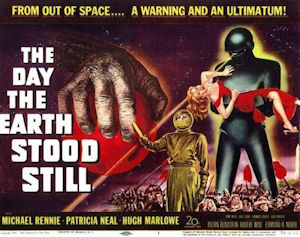

The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951) - Sci-Fi Classic Film Review

| | The Day the Earth Stood Still |

You know the story. An alien saucer lands near the National Mall in Washington, D.C., and out of it steps a man and robot. The man is Klaatu, here to deliver an important message to the leaders of Earth, and the robot is Gort, here to demonstrate the terrible consequences of not listening. Klaatu announces that he comes in peace, but one soldier's itchy trigger finger sends him to an Earth hospital, where Klaatu is informed that getting all the world leaders together in a single place to hear his message is impossible. Having no patience for mankind's petty squabbles, Klaatu effortlessly breaks out of the hospital, assumes a new identity as Mr. Carpenter, and befriends a single mother and her son. He then gets the world's attention by turning off nearly every electronic device on the planet at once. On his way to a meeting of the greatest scientific minds of the age, though, Klaatu is gunned down by an overzealous military and, as a result, Gort awakens to enact justice.

The story really starts a few years after World War II, though, with early Cold War paranoia dominating global politics. Producer Julian Blaustein got it into his head to create a film that used science-fiction to offer a thinly-veiled plea for international cooperation. Blaustein, a new hire at 20th Century Fox, wasn't an anti-war zealot by any means; during the war, he had made training films for the United States Army Signal Corps. However, with the Hollywood blacklist growing and HUAC hearings on the rise, Blaustein knew that things were getting out of control, so he scoured popular science-fiction stories of the time and found Harry Bates' "Farewell to the Master." Blaustein hired Edmund North to write a screenplay using Bates' short story as a basic template, and former RKO editor Robert Wise was then tapped to direct. That's how 1951's The Day the Earth Stood Still was born.

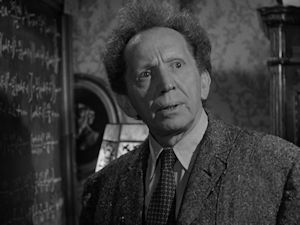

| | Notable fact: for several years, actor Sam Jaffe was blacklisted by Hollywood as a communist sympathizer |

Though he escaped the scrutiny of the House Un-American Activities Committee, Wise was a self-professed anti-military liberal, and as such, he was the perfect man to direct. Though his biggest claim to fame in those days was his Academy Award nomination for editing Citizen Cane, Wise was known more in Hollywood circles as a workhorse who thrived under the studio system making B-grade films. The Day the Earth Stood Still would be his first high-profile production, but over the years, he would make other massive hits like West Side Story and The Sound of Music, alongside other science-fiction tentpoles like The Andromeda Strain and Star Trek: The Motion Picture. Wise's directorial philosophy was one of suture, of keeping the filmmaking as invisible as possible to the audience by avoiding stylistic flourishes and distracting formalist elements.

Wise's realist directing, though, is just one of the many ways The Day the Earth Stood Still is as effective as it is. Also worth mentioning are Bernard Herrman's trend-setting score and the casting of then-unknown Michael Rennie, with his uncanny look and acting method that proved perfect for the enigmatic alien Klaatu. No matter what you attribute it to, however--be it Blaustein's vision, Bates' original story, Wise's directing, North's script (which we'll get to in a moment), the cast, the music, the political message, etc.--there's no denying that this film's success set the template for over a decade of science-fiction, cementing some tropes we still see today.

| | Don't mess with the Gort |

There's also the robot Gort to consider. He embodies Wise's philosophy, with a minimalist design that remains as iconic today as it did in 1951, but it is what he represents that makes Gort so unforgettable: he is nothing less than the personification of Mutually Assured Destruction. When the resurrected Klaatu finally delivers his message to the assembled scientists at the film's conclusion, he describes Gort as representative of a galactic army of autonomous robots created specifically to unilaterally maintain peace, capable of reducing any planet that threatens violence "to a burning cinder." Taken literally alongside the film's political message, it seems incongruous--the use of a powerful army of international (interplanetary) peacekeepers that answers to no authority feels like the exact opposite of an anti-military film--but taken as an allegory for nuclear warfare, it makes perfect sense. Indeed, if there's one thing we learned from the Cold War, it's that the threat of worldwide obliteration at the hands of nuclear weapons keeps us, however perilously, from falling into another World War.

While the anti-war theme is obviously subversive to the political tides of the time, Edmund North also managed to sneak in another layer of subversion that increases the film's power even more: it's a Christian allegory. This is one of those things that seems obvious once it's explained--so obvious it's a wonder anybody can miss it--but even the director, Robert Wise, failed to notice it until after the film was released. In case you don't know what I'm talking about, look at the film's story thusly: it's about a man (who calls himself "Carpenter") coming down from the heavens with a message about how we should treat each other with kindness, who is then killed by a hostile government before being resurrected and having one last chance to tell those who will listen that violence will be met with cosmic retribution as he ascends back to the sky from whence he came. In other words, Klaatu is Jesus.

| | Klaatu isn't exactly subtle |

If you can forgive the gross oversimplification of American politics, these two parallel allegories approach things from both the anti-war liberal left and the Christian conservative right and converge on the same, universal theme that history has since borne out to be not only prescient but true: if we don't work together, we will destroy ourselves. This theme dominated science-fiction for decades after The Day the Earth Stood Still, and continues to pop up in science-fiction today.

As an adaptation of "Farewell to the Master," the film is almost unrecognizable. The only returning characters are Klaatu and Gort (though the robot is shrewdly renamed from "Gnut"), but they are significantly different from their literary counterparts. Bates' original story has none of the political overtones or religious allegory, and its most important twist--the robot's supremacy--is pretty much lost. Once you know that The Day the Earth Stood Still started as an anti-war film first and became an adaptation second, it makes sense that it doesn't stay true to what Bates wrote.

However, as a film on its own merits, The Day the Earth Stood Still is one of the greatest science-fiction films of all time, probably better, all things considered, than its source material. Not only does it have a timely, provocative message with multiple possible interpretations, it also manages to be relatively easy for casual audiences, thanks to Wise's directoral choices to keep things simple and grounded. It's also famous for containing the most quoted line of alien gibberish of all time: "Klaatu barada nikto." While it wasn't the most profitable science-fiction film of 1951 (that would be The Thing from Another World), it was easily the most influential. One cannot overstate the importance of its legacy on not only science-fiction or on film of the 50's, but also on American culture itself.

Next, we'll look at Scott Derrickson's 2008 remake starring Keanu Reeves as Klaatu. Don't let it be said that I don't suffer for my readers.

-e. magill 1/17/2019

|

|