20,000 Leagues Under the Sea by Jules Verne - Sci-Fi Classic Review

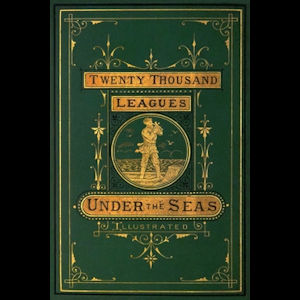

| | This is the cover of the original James Osgood English edition, which is exceptionally rare today; a first issue in good condition is worth around $10,000 |

Science-fiction in the mid to late eighteen hundreds is dominated by two names: H.G. Wells and Jules Verne, the unquestioned grandfathers of the genre. Though it is tempting to delineate between the two--to talk about how one pioneered soft science-fiction and the other hard, how one was more accurate in his predictions than the other, or how one used science as a stepping stone to the more fantastical side of speculative fiction while the other used it for a means unto itself--the two are far more similar than different. Neither of them invented the science-fiction novel--Shelley did that before either was even born--but they both pushed it into its own genre in a way that no other popular writer could. Moreover, they were doing it through the biggest niche genre of their age: adventure.

Wells' early sci-fi works--The Time Machine, The Island of Dr. Moreau, etc.--are all adventure stories at their heart, and Verne's most famous sci-fi works--Journey to the Center of the Earth, The Mysterious Island, etc.--are no different. The writers have unique styles, to be sure, but they are, in essence, doing precisely the same thing: popularizing the philosophy of science by telling imaginative tales of mystery and suspense. Out of all the great books the two men wrote, the one that best exemplifies this formula is Jules Verne's 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, first published in 1870.

Telling the story of an accomplished and learned naturalist named Pierre Arronax who is kidnapped alongside his two companions by the enigmatic Captain Nemo in his futuristic submarine, the Nautilus, 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea is a love letter to both technology and the sea, to mystery as well as classification, to myth as surely as to fact. It aspires to be both thrilling and educational, to stir the minds and spirits of its readers into appreciating the importance of scientific exploration while also dazzling them with fantastic descriptions of unbelievable experiences. It's startling in its relatively high degree of futurist accuracy, but it also doesn't shy away from visiting obviously fictional subjects such as the lost city of Atlantis, which was widely considered fake even in the Nineteenth Century.

| | A fairly standard cover |

Jules Verne was a man of many literary talents, but 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea highlights one of his greatest: he was a consummate liar. Even now, a century and a half after its publication, it is impossible to parse the fictional details from the legitimately researched ones. For every interesting fact Verne throws in that was based on real scholarship, he throws in an equally plausible bit of utter hogwash that he invents from whole cloth. During my time with Captain Nemo, I spent more hours scouring Wikipedia than I did actually reading the book. That's how Verne popularizes science, by encouraging readers to look into every little detail of his incredibly detailed story.

Even things that are demonstrably fake today, like the notion that there is an underwater tunnel between the Mediterranean and the Red Sea or that there is open water beyond the glacial walls of Antarctica, were hotly debated for decades or more after the novel's publication. Other things, though, like the famous giant squid, have proven to be true even though Verne based them on little more than vague supposition and rumor. Indeed, a living giant squid wasn't caught on camera until 2012.

For everything it does right, though, the novel is far from flawless. For example, it is dragged down by its frequent digressions into taxonomy. Two of the three protagonists, including the narrator Arronax, are obsessed with the science of classification, and as such, there are pages and pages and pages, scattered throughout the novel, of lengthy, dry recitations of the kingdom, phylum, class, order, family, genus, and species of thousands--if not tens of thousands--of fish and other marine life the Nautilus encounters. It feels like, between practically every important scene, Verne spliced in a few pages of a naturalist's textbook.

| | I like this one |

There's also a pattern to how things play out that feels almost identical to a modern educational program, kind of like a slightly darker version of The Magic School Bus. One character will ask a fairly basic question about some relevant topic--like asking about the history of an island they're passing or talking about how the Red Sea formed as the submarine makes its way into it--and the other characters in the scene will then answer the question with the enthusiasm of good primary school teachers. This will happen either before or after a big event that directly relates to the topic. These are the moments where Verne displays his deep knowledge, and though they are entertaining and educational, they don't feel natural or organic, and they really take away from the suspension of disbelief. (Yes, he was writing for a younger audience--and there's an argument to be made that writers like Verne discovered the formula that modern educational programs use--but I can't help but read with an adult's sensibilities, as I am, it seems, an adult.)

There's also very little dramatic tension. The story starts with a compelling enough problem--the rogue submarine haunting the oceans that Arronax and the rest of the world falsely attribute to a giant narwhal--but once the trio of Arronax, Conseil, and the unsubtly-named Ned Land arrive on the Nautilus, the problem morphs into their imprisonment, a problem two of the three characters are perfectly content to ignore for almost the entire rest of the tale. The mystery of Nemo and the promise of an explanation for his bizarre behaviour certainly holds the reader's attention, but--spoiler alert--that explanation doesn't come in the pages of the novel. (It comes in The Mysterious Island, the pseudo-sequel to 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea.)

| | If you can read French, this would be a cool hardback to have around |

The closest thing to a character arc involves Arronax's temptation to succumb to Nemo's will. The two men share a profound love of the natural world, especially as it exists in the sea, but Nemo also festers a strange hatred for mankind for reasons that are only hinted at in the final pages of the book. However, since Nemo's obsession has an external cause that doesn't relate to Arronax, the dramatic desire to "become" Nemo has pretty clear limits, and it is never called into question that, eventually, Arronax will side with his friends over Nemo. Ultimately, then, his character is static, not dynamic, only threatening to change but never following through.

Therefore, 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea represents a frustrating dichotomy. On one hand, it is a brilliant and forward-thinking work of science popularization that tells an adventure story that has become a modern legend, highlighted by the iconic character of Captain Nemo. On the other hand, it can be a slog to get through, with lengthy passages of classification and little in the way of narrative tension or character development. It's both a great novel and a fatally flawed one, and though I have no desire to read it again, I can't deny it deserves to be a landmark work of early science-fiction.

-e. magill 3/14/2019

|

|